Julian Jaynes explores the idea that the “self” is installed via culture, not emergent by default from our minds. In his book, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, he explores a beautifully complex and wide-ranging theory that suggests that we developed internal monologues as a mechanism of coordination and control.

As group sizes in early human evolution increased, it followed that coordination over team sizes and time was ever more important. Instead of always being in a group of people that moved together, independant teams and individuals would operate in parallel, but in order to stay on task, Jaynes suggests that we developed the ability to hear voices to guide our work. “Go and fetch some driftwood” repeating in the mind of an early hunter/gatherer would ensure task adherence (albeit I’d be surprised if they had fully-formed English knocking about at that point.)

Over time, this generative capability expanded to include the voices of those that had died and metaphysical forces, or gods. This means that early humans may have literally heard the voices of loved ones and gods, and this was a key driver of culture and therefore development. This was facilitated by a bicameral or two-chambered physiology – a speaker and a listener in the mind, which eventually broke down into a single monologue-making-mind (and led to the “self” that we think of today.)

Such a capability would also likely lead to the splitting of identity – going from a small group where a band of humans operates as a single unit – growing to tribes, and then chiefdoms and eventually states (as outlined in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel) – individualism would become more important for the continued growth of said group. Culture is that which binds a group together – in a group of 10 that are all related the “culture” the history they all share, but in a group of 500, some cultural identity must be installed to foster group cohesion.

In such a group size however, specialisation arises (again from Diamond’s research, these group sizes can only occur in food-producing units, which means a food surplus, which leads to specialisation.) And specialisation can be taught using the meme of the self. You are a farmer. You are a fisherman.

In this way we lay down the foundations of a wall between ourselves and direct experience. So adept are we at this, that many (most?) people cannot even process their bodily emotions, let alone appreciate the beauty of existence in each moment.

In service of the group, we installed the roots of individualism, but in doing so did we inadvertently develop a parasite in the core of our minds? To have a self necessitates a boundary between the environment and the person. In fact, this very framing of “environment” vs. “inhabitants” has, in my mind, led to much of the destruction of nature we see around the world. We see ourselves as distinct from the environment, commanders of resource there to be used by us, rather than as an intrinsic part of it.

Selfhood is so enchanting, so perfectly self-referential, self-sustaining and well-adapted to our biology that it would seem almost everyone is using, or used by it.

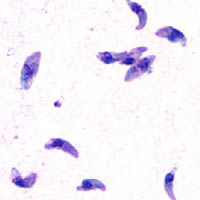

Toxoplasma gondii: This parasite literally changes host behavior to help its own reproduction. It makes infected rodents less afraid of cats (and even attracted to cat urine), making them easier prey. The parasite can only complete its life cycle in cat intestines, so this behavioral manipulation is incredibly sophisticated.

But is it possible that selfhood is just a very well-adapted system of ideas that we install at a very young age because we believe it to be the natural state? We give everyone an individual name and say it enough times to them that they affix their memories to it – around a spine of self.

Attachment to self is a deep well of suffering (death fear, loneliness, material obsession.) Modern individualism is built around this, as well as its inverse (self-development, ambition, personal growth.)

I should say at this point that I’m not suggesting the self has no value – being identified with a self is an incredibly useful tool – but perhaps it’s just that – a tool. We can exploit the parasite: you went for a run becomes “you are a runner”, which helps curate the stories your internal voice tells you. In my self-development practice this has been an incredibly useful tool.

But we should recognise that this is a tool we can put down – a sword is useful for battle, but we would never consider identification with the sword. We should start selfing when useful, but seek to loosen our grip on the hilt of the self when the day’s specific battle is fought.

The balance of self-development and self dissolution is something I’m working on understanding better, and I think the idea that I am not the self is particularly fertile ground for growing in understanding.